SOLO EXHIBITION - 2014

fragile equilibriums

... at each moment our ideas express not only the truth but also our capacity to attain it at that given moment ... our ideas, however limited they may be at a given moment − since they always express our contact with being and with culture – are capable of being true provided we keep them open to the field of nature and culture which they must express ... The idea of going straight to the essence of things is an inconsistent idea ... what is given is a route, an experience which gradually clarifies itself, which gradually rectifies itself and proceeds by dialogue with itself and with others. Thus what we tear away from the dispersion of instants is not an already-made reason; it is, as has always been said, a natural light, our openness to something. What saves us is the possibility of a new development, and our power of making even what is false, true − by thinking through our errors and replacing them within the domain of truth.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1)

fragile equilibriums - Alta Botha, 2014

Michaelis School of Fine Art, Cape Town, South Africa

Working process.

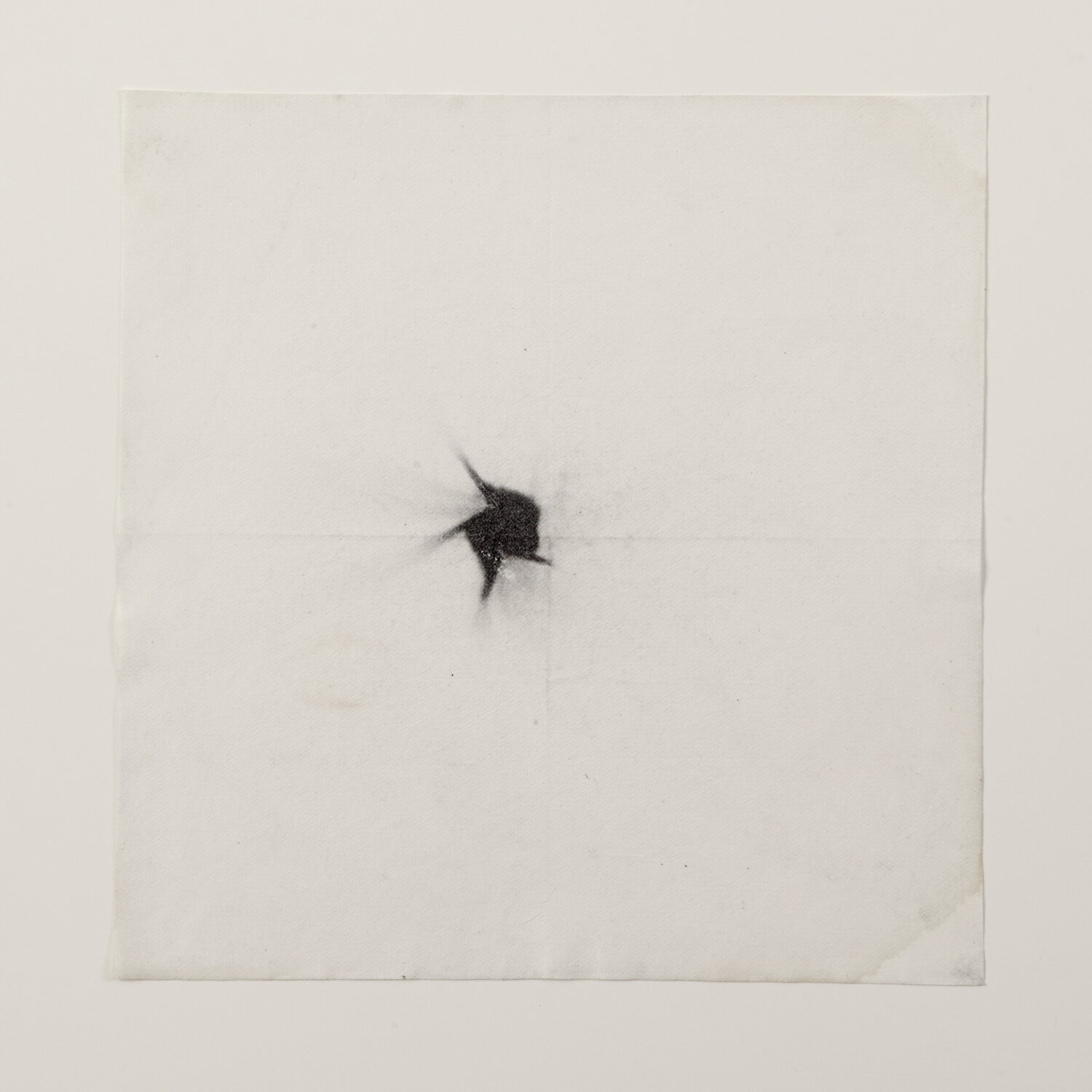

daily servings, 2012 (Selection)

Charcoal fallout and used disposable serviettes

Variable – approximately 33 x 33 cm

mark(er) I, 2013 (Detail)

Filter paper, found and activated charcoal, cotton thread and pins

Variable – approximately 370 x 340 cm

mark(er) I, 2013 (Detail)

Filter paper, found and activated charcoal, cotton thread and pins

Variable – approximately 370 x 340 cm

mark(er) II, 2013 (Detail)

Filter paper, found and activated charcoal, cotton thread and pins

Variable – approximately 370 x 240 cm

mark(er) II, 2013 (Detail)

Filter paper, found and activated charcoal, cotton thread and pins

Variable – approximately 370 x 240 cm

single utterings, 2013 (Detail)

365 Miniature filterings, medicinal activated charcoal, filter paper cut-outs, filter fabric and entomology pins

Variable – approximately 40 x 180 cm

single utterings, 2013 (Detail)

365 Miniature filterings, medicinal activated charcoal, filter paper cut-outs, filter fabric and entomology pins

Variable – approximately 40 x 180 cm

cover(ture). From the murmurings of the mind series, 2013

Tissue paper, activated charcoal, Indian ink, surgical gauze and micropore plaster

55.5 x 168.5 x 9 cm

g(r)asp. From the murmurings of the mind series, 2013

Chinese rice paper, activated charcoal, Indian ink, surgical gauze, cotton thread and micropore plaster

44.5 x 99.5 x 7 cm

hide. From the murmurings of the mind series, 2013

Fabriano paper (200 gsm), charcoal, activated charcoal, Indian ink, mull, cotton thread and micropore plaster

44.7 x 100.4 x 4.2 cm

dwell. From the murmurings of the mind series, 2013

Canson paper (180 gsm), charcoal, activated charcoal, Indian ink and fabric mesh

45.3 x 98.3 x 3.3 cm

seek. From the murmurings of the mind series, 2013

Canson paper (180 gsm), charcoal, activated charcoal, Indian ink, cotton thread and micropore plaster

44.3 x 97.5 x 4.7 cm

lie. From the murmurings of the mind series, 2013

Fabriano paper (180 gsm), charcoal, activated charcoal, Indian ink, cotton thread, linen thread and micropore plaster

47 x 102 x 4.2 cm

find. From the murmurings of the mind series, 2013

Canson paper (180 gsm), charcoal, activated charcoal, Indian ink, linen thread and micropore plaster

42.7 x 93 x 4.2 cm

mind. From the murmurings of the mind series, 2013

Fabriano paper (160 gsm), charcoal, activated charcoal, Indian ink, mull, cotton thread, linen thread and micropore plaster

43.5 x 99.8 x 4.2 cm

who is speaking to whom, why, and for whom I, 2013

Rives paper (300 gsm), compressed, found and activated charcoal, Indian ink and household furniture wax

400 x 213 cm

who is speaking to whom, why, and for whom I, 2013 (Detail)

Rives paper (300 gsm), compressed, found and activated charcoal, Indian ink and household furniture wax

400 x 213 cm

who is speaking to whom, why, and for whom II, 2013

Canson paper (120 gsm) and medicinal activated charcoal

800 x 150 cm

balm(y), 2013

Sand paper, linen thread and Canson paper fibres

45.2 x 120 x 5 cm

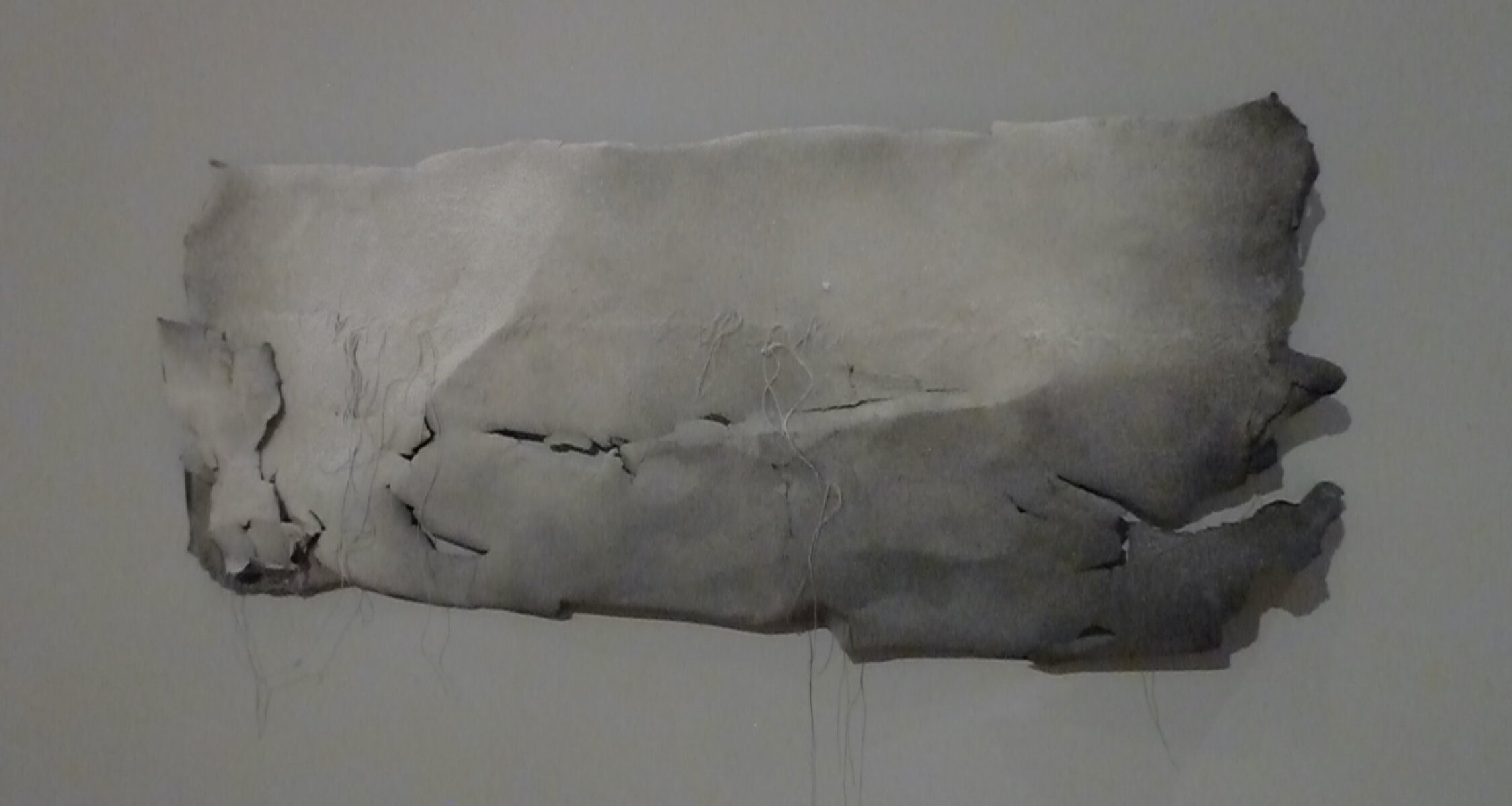

lull(aby), 2013

Fabriano paper fragments, cotton thread and micropore plaster

55 x 130 cm

In my art making I use paper as a primary material. I erode its materiality, perforating the surface in anticipation of whatever may be revealed, searching for new ways of seeing. What emerges are contradictory concepts: reduction and accretion. These mechanisms exist in counterpoise with one another, yet the boundaries are blurred, indefinable. The fragile balances that operate within the mechanisms of power are similarly contradictory. It is here that this exploration resides, moving away from what has gone before – as Merleau-Ponty proposes above – taking an ongoing ‘route’, anticipating the possibility of new developments.

How do our narratives unfold when information − new and stored − is brought into the picture? I believe that the manner in which we attempt to contextualise, rationalise and control our life situations can be equated to a filtering system. The continuous assault of new information and experiences leads to a revisitation of personal and collective history and memories. When recalled, this stored knowledge is reconsidered. Perceptions of what is ‘true’ or false, ‘real’ or imagined or ‘fact’ or fiction are adjusted and readjusted in an attempt to comprehend and make decisions. These processes involve active engagement, as Merleau-Ponty observes. (2)

In response, ‘filtering’ as a method offers collectively a concept, a structure and a process of production. My choice of materials − charcoal as ‘filter’ (3) and various kinds of paper used as both surface and support – acts as a limit, a controlled framework within which to operate. These self-imposed limitations, to me, symbolically link to the limitations of women in a patriarchal society and the limiting structures and mechanisms of power.

A minimalist approach (4) to art making allows for the reduction of ‘noise’ and the elimination of excess. It pushes me out of my comfort zone of working in mixed media and familiar methodologies. Limitations of media intensify my focus and therefore require me to delve deeper, continuously striving to find and develop new possibilities, leading to new insights and engaging in a process of ongoing incremental unfolding. These fragile equilibriums operate within complex processes of unconscious and conscious awareness – constantly shifting, adjusting and readjusting.

By engaging with charcoal as substance, it revealed itself as the concrete product of a process of transformation. In this sense, charcoal marks possibility within fiery destruction. I find in charcoal not that which is lost in the fire, but the physical ‘mark’ of the fire that remains burning − charcoal contains the ‘memory’ of the fire and has come to represent an acknowledgement of that which can be valued and reclaimed from a consuming and destructive force. Charcoal, for me, remains a hopeful medium – as a ‘vibrant matter’ (5) it has the capacity or power to effect change. In this sense I am pointing to a process that is transformative.

While considering power as either a destructive force or a constructive capacity, processes of retrieval, reconstruction, restoration and reparation became important aspects of the work. Sewing, by hand, explored as a mark and as a conveyor of meaning – in particular the mending stitches my beloved grandmother used when I was a child – is linked to care.

This body of work represents the hope to create a new context and a symbolic ‘place’ for resistance – continuously setting up new balances for power relations.

Merleau-Ponty, M. 1964. The Primacy of Perception and its Philosophical Consequences, in Edie, JM. The Primacy of Perception, and Other Essays on Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, p. 21.

Merleau-Ponty, 1964: 21.

Charcoal is a natural filter based on its porosity, which provides an extended surface area. (science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/energy/question209.htm)

Although the visual language developed here is most closely related to the art historical context of minimalism and related movements, and the work visually or formally relates in terms of a reduction of means, use of everyday and industrial materials (found and activated charcoal, and filter-, wax- and sandpapers from industry) and the use of repetition, my concerns are different to those of prominent minimalist artists.

A ‘vibrant matter’, Jane Bennett argues (in Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. 2010. Durham: Duke University Press, p. xiii), is materiality that has the potential to impact on another ‘body’ or material. It is therefore not static, passive, ‘dull’ or inert. It has the capacity to influence and effect change.